Producing a multi-million dollar, state-of-the-art health facility is more than just identifying a need, putting pen to paper and constructing a building.

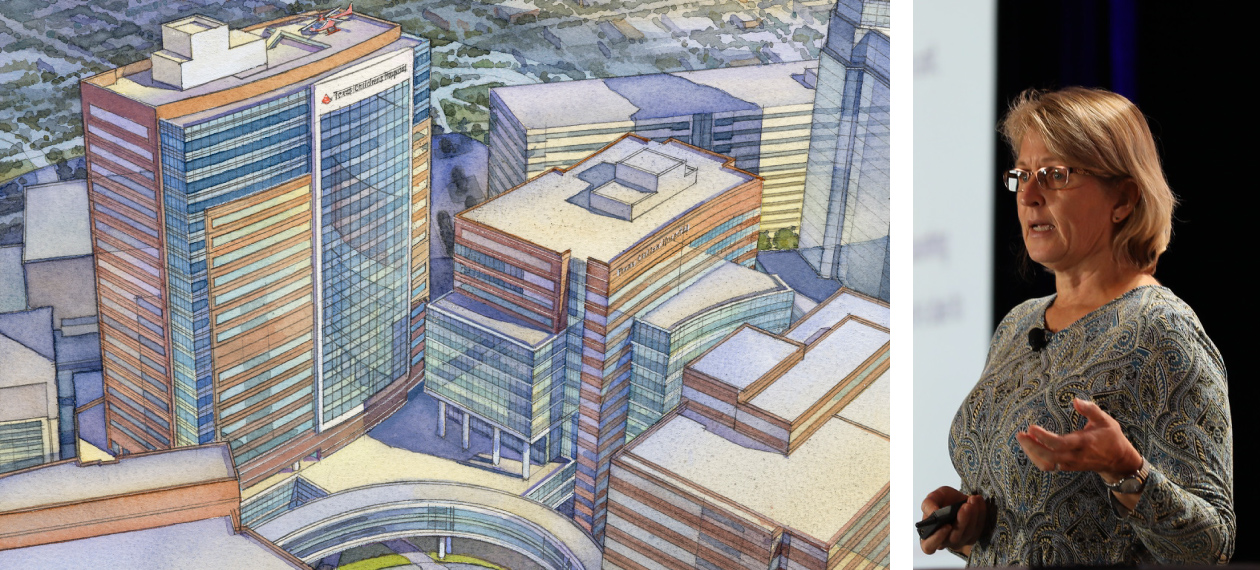

As Jill Pearsall, vice president of facilities planning and real estate at Texas Children’s, shared with HealthSpaces, building the right hospital or other healthcare facilities today means hours of conceptualization, planning, collaboration, stakeholder input and simulations.

"A lot of times we ask customers what they want, but we're like 'yeah, yeah, yeah' but we know better," Pearsall said. "Or the design team will say we're going to do this, we benchmarked this but they haven't asked 'who are we working for?'"

Reconfiguring the design and construction process required time and effort, but in Pearsall's experience with the construction of Texas Children's Legacy Tower, it transformed the building processes, ensuring needs were met and concepts are realized without expensive change orders and outstanding issues.

Pearsall highlighted the steps it took to complete the Legacy Tower building, which opened in 2018.

Identify The Need

Texas Children’s, whose facilities portfolio encompasses 12.1 million square feet, is a healthcare system in Houston that includes three hospitals, speciality and urgent care centers, and a gamut of services, Pearsall said.

It's also where Texas Children's is located. It was determined several years ago that there was a need to overhaul the facilities housing Texas Children's critical care services.

"We had some serious problems," Pearsall said. "Our pediatric ICU was built in 1991, it was dark, noisy and crowded."

Over the years, the organization had made due with what they had, including rolling out layered technology. However, that just added more equipment to the environment.

"Our critical care medicine medical director said it best, 'Twenty-five years ago, these kids weren't surviving,'" Pearsall said. "So that means we have a lot of equipment and interventions."

Finding space for that equipment and technology was not an easy feat.

"It's great that we can save their lives, but that has some serious consequences on our space," she said, noting that rooms in the critical care space ranged from 161 to 270-square-feet.

"There was no bedside space for families, caregivers, or procedures," Pearsall said. "It was not a great environment."

Perhaps the most distressing part of the facility was that care was being denied to some.

"We were having to turn away children that needed our help," Pearsall said. "That is absolutely not our mission."

What Can Be Done?

With the need obvious within Texas Children's, Pearsall and her team's attention turned to what could be done to fix the issues.

In the end, they determined they would complete a vertical expansion to create the Lester and Sue Smith Legacy Tower

The six-story base would eventually undergo a 19 story vertical expansion to specifically provide critical care space for patients.

"We were going to build 138 critical care beds for pediatrics," Pearsall said. "How do you decide what to do for critical care of the future? There's a lot of opinions, input and feedback going both ways."

Early Mock-Ups

After determining what the building would be used for and the number of rooms needed, attention was turned to what those spaces would look like.

TMC mock-up before design phases

Pearsall said the team began creating an early mock-up of the critical care floors to first determine just how big rooms needed to be.

"What the mock-up told us was that we needed and desired 360-degree access to the bed and space for all the equipment," she said.

The mock-up generated a room that was 289-square feet just for patient space.

"That was bigger than any of our rooms," Pearsall said.

Getting Input

With major changes coming to Texas Children's and those who provide care, the team went straight to clinicians for input on their workspace.

Conducting a "Blitz Week," Pearsall's team gathered all of the clinicians who would be working in Legacy Tower to determine their needs, talk about current workflows and what the future needed to be.

"It was a very long week," Pearsall said. "It engaged hundreds of people, with a lot of coffee and an incredible amount of input."

Looking At Others

With input from clinicians at Texas Children's in hand, it was time to find similar facilities to check out.

The team, along with several of the Blitz team participants, went to UCSF Benioff Children's and Lurie Children's.

"We said, 'what are you guys doing that we could learn from," Pearsall said of the visits. "So we listened, we listened to our partners."

The tour focused on the operating rooms, technology areas, staff space, family-centered areas and the ICU.

"We also focused on the actual environment and how we served our families," Pearsall said. "We got a tremendous amount of feedback on that and layered it with the Blitz feedback."

Going To Families

"Then we said, 'we need to listen to some of the actual customers we serve," Pearsall said. "We picked focus groups specific to critical care and specific to our heart center. We brought them in early and asked for guidance on how to design and what we needed to provide."

The cross-functional group included 15 families who had children at Texas Children's for anywhere up to two-and-a-half years, those who still had children at the center and those who lost a child.

During the discussions, families let their preferences be known. For instance, in respite space, families don't want to go outside and go shopping. Instead, they wanted to just get away, to walk around.

The discussions covered all elements of the floor and patient rooms.

Pre-Construction Simulation based on feedback

Parents described the patient room as their home, ‘it is my child's bedroom. Let me do what I need to do to make it their home,' Pearsall recalled hearing.

When the topic turned to grieving, the families also had strong opinions.

"We had looked into having bereavement rooms," Pearsall said. "The families were outspoken, 'do not make me go to that room.'"

"They said, 'why would you build something that is never going to be used,'" Pearsall said. "We would have built those rooms had we not asked the questions."

Building Simulations

In all, the project received more than 2,000 data points of feedback for design.

With that information in hand, the team began creating simulations of the building, starting with a tabletop simulation.

"We really focused on efficiency, patient safety and involved all the physicians," Pearsall said. "It was asking us how do you want to work."

The tabletop simulation allowed them to assess floor layouts, patient safety, workflow efficiency, as well as viewing the pathways for clinical teams and pinpoint any bottlenecks or risk points.

The project then moved to a pre-construction simulation in 2015 of one room and its surrounding areas that allowed the organization to really understand the patient experience.

"It was driving decisions," Pearsall said. "We built the rooms, we cut the windows, we put in the doors, pasted everything on the walls."

The purpose of the simulation was to drive design decisions, identify latent patient safety threats in rooms, and mitigate the degree of changes needed down the road.

"It was quite shocking," Pearsall said.

In the end, they rotated the PPE closet, moved the monitor position, widened windows and shrunk doors.

"Imagine if we built the first room the wrong way 138 times," Pearsall said. "That's scary. It's massive amounts of money and disruption."

The Message

In the end, Pearsall said the message of the team's process is to "get it right the first time."

To do that, they needed to put in the effort up front.

|

"Most owners want to go straight to the solution," she said. "Most architects want to start designing. But we have to stop talking, listen and ask."

The team relied on early and constant engagement, consistency and alignment of design and operation.

"What does that mean? We have the right care, right place, right time that equals patient safety," Pearsall said. "We also had engaging staff along the way. They were engaged and knowledgeable and immediately went to work."

When comparing Legacy Tower to previous construction projects, the benefits of Pearsall's process is evident.

"The original building was not done with any of this," she said. "We didn't simulate that and we had over 1,200 outstanding issues for $11.3 million."

The new building? It opened with 31 outstanding issues for a value of $165,000.

"Did we invest $11.3 million in people's efforts and time? Maybe," Pearsall said. "But we've made zero changes to this environment. To me, it was well worth that extra work."

Posted by

Collaborate with your Peers!

HealthSpaces is a community for people that plan, design, build and operate spaces where healthcare is delivered.

June 7-9, 2026 | Braselton, GA

Learn More

-4.png)

-Dec-09-2025-05-48-44-4379-PM.png)

-4.png)

-1.png)

-2.png)

Comments