Cedars-Sinai Medical Center—known to many as the "hospital to the stars," a moniker that is not unwelcome, if not entirely accurate—is a large academic medical center in the heart of Los Angeles. With 890 licensed beds and an average daily census of 930-940 patients, the nonprofit medical center is very busy, and as much as that helps their bottom line, it's also their biggest problem.

Alan Dubovsky, Chief Patient Experience Officer (CXO) at Cedars-Sinai, spoke at HealthSpaces about his work gathering and analyzing patient feedback, and how his team has used that feedback to improve the overall patient experience. The CXO is a relatively new role for hospitals, but it is also an incredibly important one. The role of the CXO is to use design principles and other strategies to enhance and improve the patient experience. Their work of the CXO also helps to identify areas of opportunity within the hospital and uses design strategies to solve the operational issues that lead to patient dissatisfaction.

Problems Every Hospital Wants

"Our major problem today is how busy we are," Dubovsky said. "My team has been trying to understand what things are most important to patients when we get as busy as we do."

Their biggest area of opportunity, he said, is finding a way to maintain a positive patient experience even at their busiest.

After analyzing nearly 90,000 responses from patient feedback surveys, they found that the most important category—and the one that suffered the most—was "care transitions," questions regarding the patients' feelings of readiness and preparedness to go home.

"Care transitions were the number one things that suffered on our busiest days," Dubovsky explained. "On average our care transition scores dropped 10 percentage points, which can be about a 30 to 40 percentage point drop in patient experience data."

The survey data revealed that when the patients were discharged during busy times, they felt rushed out the door with little opportunity to ask questions about what to do to take care of themselves once they got home. This is largely an issue of perception—the patient feels like the hospital is too busy for them to ask questions, and at the same time, they also just want to leave. But when the patient gets home and looks at the 50 pages of documentation they were given, they don't know what to do. Then they end up calling the hospital or getting readmitted, backing up the system once again.

Patient reporting his experience

Another issue that patients had with the care transition process was the lack of opportunity for input in their discharge readiness assessment. In short, the patient may clinically be ready to go home, but they don’t necessarily feel ready to go home; once again, this deals largely with questions they still have concerning their aftercare.

In order to address these negative experiences that patients were reporting, Dubovsky and his team designed several new processes to improve how patients feel as the hospital gets busy. In his talk, he focused on two specifically: utilizing technology to include the patient voice in the process of discharge planning, and the "infamous" discharge lounge, a pleasant-sounding name for a room that serves as a dedicated holding pen for patients being discharged, which has consistently failed at every hospital that has ever tried to implement one (Cedars-Sinai included).

"Departure Lounges" as Part of the Patient Experience

"Every hospital has tried [discharge lounges] at least 50 times and has failed 50 times," he said. "We've had as many discharge lounges as I can count. Every single time we've tried this it has been open for about a week, people like it, then they stop using it, it fails, it closes, and we move on."

Despite the bad track record, in late 2018 they found their hands forced to try out the discharge lounge model again after wildfires in Southern California had closed a hospital in North Los Angeles and all those patients were getting funneled down to the Mid-City medical center. They decided to open a lounge to have a place to keep the patients getting discharged and free up beds for new patients.

Surprisingly, perhaps to no one more than Dubovsky himself, the lounge is still open a year later. As a result, they have gained 381.9 hours of patient bed time per month, helping to free up the bottleneck in the emergency department.

So what made this time a success when so many other attempts have failed? Part of it, Dubovsky said, is that they are talking about this space a lot differently. First, they are referring to it as the "departure lounge" rather than a discharge lounge, and it is treated as part of the process where all patients go when they are getting ready to leave.

"We script that from the moment you arrive at our hospital," he said. "It is now a standard process. As a patient, if you are clinically able to, you will go to the lounge and that is where you will wait."

When they first opened the lounge they had it staffed with limited duty, non-administrative, non-clinical staff members, and the experience wasn’t helpful to patients. There were also still patients that didn't want to leave the comfort of their beds just to go sit in a chair in another room with several other people. But then they added a full-time nurse to staff the departure room, and that person is able to go through and explain all of the patient's paperwork, schedule follow-up appointments, get them activated in the patient portal, and answer any other questions they have.

"For patients, the value added step here was the ability to continue that discharge conversation in the lounge," Dubovsky said. "When you are thinking about creating these zones for patients to be in, the value added step for them needs to be there. If it isn’t, patients will be the first ones to call you out and say they’re not going there. Now we have patients that actually request it because it gives them that hour or two of continued clinical education."

Now, the departure lounge fulfills what was perceived to be a vital missing step in the care transition process and gives patients ample time and one-on-one opportunity to ask any questions they have regarding care and follow-up. And as an added bonus to the hospital, it also frees up beds faster.

Technology Gives Patients a Voice

An even bigger issue at Cedars-Sinai was that patients were most upset at what they felt was their lack of voice in the discharge process. Dubovsky and his team found a way to use technology to address that.

Every morning the nursing units would conduct "progression of care rounds" (POCR), during which time the doctors, nurses, case managers, social workers, nutritionists, and anyone else dealing with the patients would discuss each patient's readiness for discharge…except for the patients themselves.

"At no point was the patient’s voice part of that process," Dubovsky said, so patients would get cleared for discharge but not have a way to get home or have a caretaker ready for them. The solution was to put a simple tablet in each room, and on this tablet every morning patients take a simple survey asking them on a scale of zero to five how ready they feel to go home. This information is then included on the POCR worksheets. For anything under a four or five, a nurse or case manager will follow-up accordingly to address that patient's needs or concerns until they do feel ready.

Dubovsky recounted a story of one frequent patient who had reported a zero because she was in so much pain but didn't know who to tell or how to tell them. By the time she was released, she was at a five, and on that final survey she commented, "Thank you so much for taking my voice into account; this is the first time I’ve been at Cedars-Sinai where I felt like I had a say in when I went home."

"You don’t want patients to dictate when they’re ready to go home," Dubovsky cautioned, "but it’s the perception of the patients having a voice in that process that made all the difference for us."

Turn Feedback into Data You Can Use

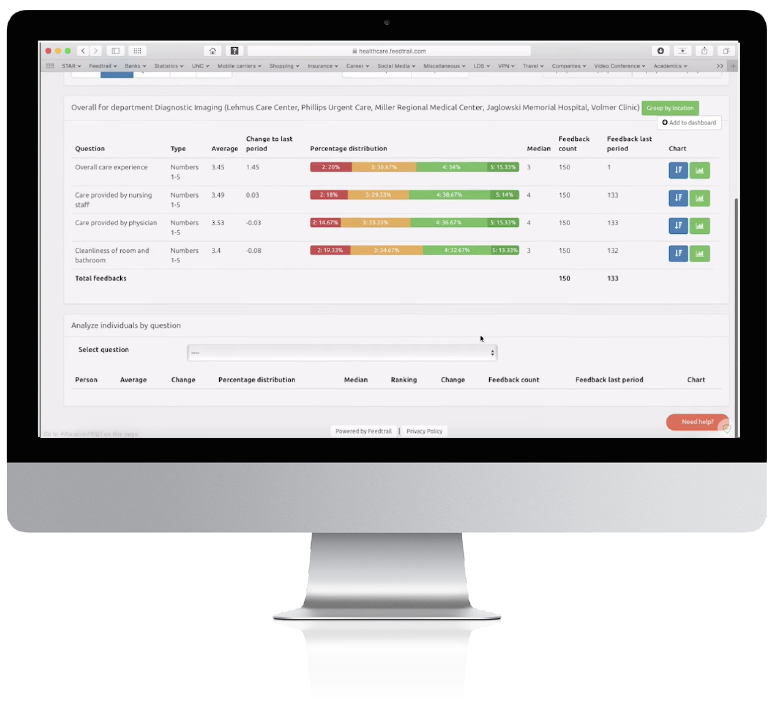

Dubovsky said they know these new processes are working because they have such a robust patient feedback loop, collecting 300,000 post-encounter patient surveys each year, and they work with vendors like the patient feedback analysis startup Feedtrail to analyze that data and turn them into actionable insights.

Feedtrail Software

"Working with companies like Feedtrail is critically important because what we’re doing is journey-mapping all these different kinds of patients to figure out what is the right moment when they want us to know how they're feeling," said Dubovsky. "A stage four cancer patient and a new mom get the same survey on the same day for their hospital experience and will tell us entirely different things, so I really want to work with companies that are interested in trying to figure out how to gather this information differently."

Another way they know it's working: over the last 18 months, their national ranking in those care transition scores are now in the top 10 percent in the country in some areas.

Dubovsky concluded his talk by urging all of the people working in facilities and hospital design to try to partner up with a patient experience team as much as possible to ensure that all of the planning, designing, and building that is being done for patients also includes the voice of patients.

Posted by

Collaborate with your Peers!

HealthSpaces is a community for people that plan, design, build and operate spaces where healthcare is delivered.

June 7-9, 2026 | Braselton, GA

Learn More

-4.png)

-Dec-09-2025-05-48-44-4379-PM.png)

-4.png)

-1.png)

-2.png)

Comments