Between inflation, labor shortages, supply chain issues, and the ever-looming threat of COVID-19, it’s not exactly the easiest time in the world to build new healthcare facilities. As design and construction leaders across the healthcare industry return to the work of building its future, they must evolve new ways of dealing with obstacles that inconveniently keep evolving with them.

Fortunately, they’re not alone. During the “State of Construction” discussion at HealthSpaces, industry leaders came together to share their own approaches to key challenges in healthcare construction. Moderated by Jordan Cram, CEO of Enstoa, the panel included James Mladucky, VP of Design & Construction at Indiana University Health; Walter Jones, SVP of Campus Transformation at MetroHealth; and Mandy Hansen, Senior Director of Planning, Design and Construction at Seattle Children’s. With a focus on operational techniques the panelists bring to the problems they face, the conversation covered issues in recruitment, automation, procurement strategies, and community.

“Our Team Members Are Our Best Recruiters”

All three panelists acknowledged the obstacles they face staffing up in a hot market. As Jones explained, competition from Cleveland's other hospitals makes recruitment a perpetual challenge, though MetroHealth's status as a shiny newcomer has proven attractive to job applicants on the non-construction side.

Hansen described similar challenges in Seattle, where project managers tend to flock to owner's rep firms that offer better salaries, bonus structures, and leadership opportunities. On the other hand, she and Mladucky have both found retention to be a relative breeze, which they attribute to the power of their organizations' missions to build interesting, challenging projects that serve their communities. "Once we get people in the door, we keep them," Hansen said. "It's very rare that we have PMs leave.”

Asked about the benefits of recruiting nationally versus recruiting locally, Hansen added that casting a nationwide net is an important part of Seattle Children’s focus on diverse staffing. Mladucky said he tends to stay in-state, where it helps that Purdue has a robust construction management program and Ball State University has a high-quality architecture school, both of which enjoy a steady pipeline to IU’s design and construction team. It also helps that his existing employees like their jobs. “Our team members are our best recruiters,” he said.

Keeping Up with the Robots

Turning towards the industry’s ongoing embrace of automation, the panelists agreed that the benefits are clear – as is the fact that they require a careful, evolving approach. Mladucky said that one of IU's contractors uses robotic bricklayers, which are especially advantageous in a market short on masons. Drones, similarly, offer unbeatable resources when it comes to site mapping. But as the world changes, so must the industry's standards.

"It's a challenge to keep it up," Mladucky acknowledged. "Our BIM standards are constantly evolving as we learn and as we change technologies – or as technologies change." That’s why IU’s project managers work closely with its BIM manager, who diligently ensures those standards are followed across its portfolio.

Then there are the human considerations. As Seattle Children’s looks toward using automated technology in the coming years, Hansen expects the process will involve complicated conversations with labor unions “about what might seem like taking jobs away from people, but we don’t have the people to fill the jobs.”

In a similar vein, Jones stressed that there will always be a balance between human and robotic construction (at least, until someday far in the future when robots can build entire buildings on their own). For MetroHealth, part of that balance is taking a “design-neutral approach” to building medical facilities: a form of standardization wherein individual rooms and broader configurations are designed to accommodate changes that might occur later in the building’s life.

“Over time, as you change processes or as departments move from one area to the other, I don't have to change any of the rooms,” he explained. “I can reassemble that core any way I need to in the future quite easily, with a whole lot less disruption than you would normally have if everything was part of the walls.”

Better Living Through Diverse Procurement

Next, the panelists discussed how their internal procurement teams are evolving. At IU, Mladucky explained, the design and construction team has three dedicated procurement leads: one focused on supply chain matters, one focused on procurement of construction and professional services, and one focused on DEI concerns.

“Those three people are the ones that team up to look at how we can procure and make sure that we're not only getting the best price, but the best value in inclusive, diverse work,” he said, “and that we are advancing into those kinds of things systematically.” Incentive bonuses for leaders across the IU system are tied not only to whether they deliver projects safely, on time, and on budget, but also to whether they hit DEI requirements.

At Seattle Children’s, Hansen said, her team is evolving its procurement methodologies to better meet its DEI goals. One approach is to invest in the future of smaller, more inexperienced firms by partnering them with larger ones. "What we find is the smaller firms don't have the structure they need to manage their building system, all those things that happen with a really big project," she said. "How do we start to pair them up so that they start to get that experience and can be part of that project but then don't have to carry that overhead?”

Serving the Community

Finally, Cram asked the panelists what strategies they use to engage with their respective communities. Jones explained one of the dilemmas MetroHealth faced as it began work on its new, $767 million hospital: the company was under (reasonable) pressure to keep its acquisition and procurement spending in the local economy, one that isn't exactly suited for a project of this nature.

"We are looking to invite people into the hospital, to interact in the hospital; to create a destination for health and to be that hub for the community and the state."

“We're a very large hospital project; Cleveland is not the hotbed of large local design firms, engineering firms, or construction companies to do projects of that scale,” he said. “We have some, but they're a precious few, and of course they're the ones that get most of the work at that scale – much to everybody's chagrin.”

Fortunately, an institution of MetroHealth’s size has ways to make up for it. In 2019 the system launched its Institute for H.O.P.E. (Health, Opportunity, Partnership, and Empowerment), an effort to address social determinants of health by bringing resources and opportunities to the broader community.

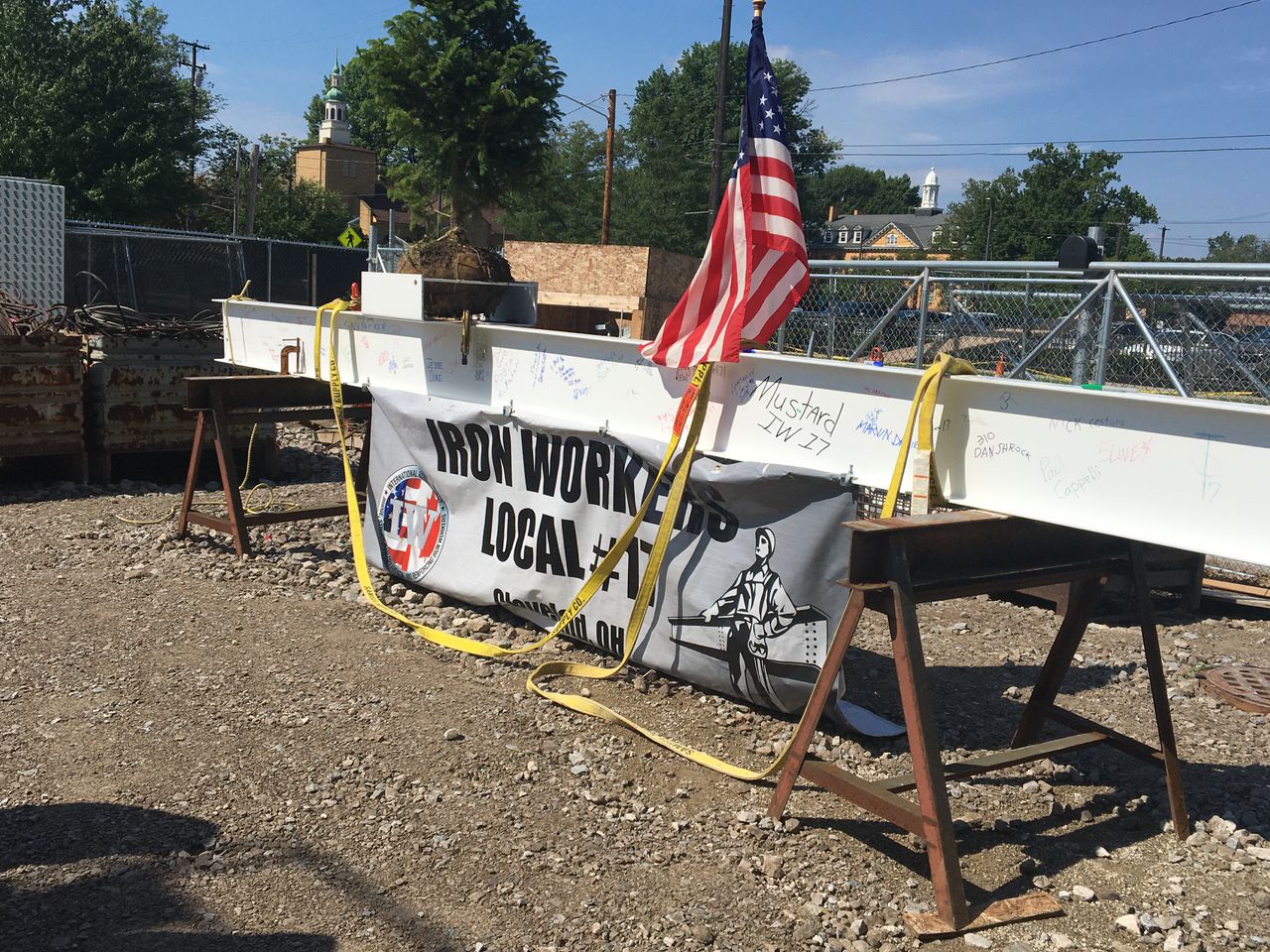

Metrohealth Final Beam

“We have a high school in the hospital. We sponsor bus rapid transit routes with the local public transit agency. We're out in the community,” Jones said. “We have a nonprofit called CCH that is working with local developers. We're building low-income housing on our property, and soon senior living housing across the street on our property.”

Seattle Children’s, meanwhile, is required by local law to incorporate community benefits into its very design. “We have to provide local access to our campus; walking trails. We have to have a certain amount of green space,” Hansen explained. The hospital also maintains a standing advisory committee composed of local residents, with whom it consults in the early stages of every new development.

"We have to carefully balance what we need and what the neighbors think we're allowed to have," she said. "How do we create support for the development we need to do within the greater community, so that that group will come to the table and have productive conversations with us?”

In downtown Indianapolis, where the average life expectancy is only 68 years, Mladucky’s team is planning an approach similar to MetroHealth’s: the creation of a “health district” designed to invest in social determinants of health in the region. To that end, IU's government affairs team is in the midst of a massive community outreach effort, meeting with (by Mladucky's estimate) more than 160 local groups.

“We are looking to invite people into the hospital, to interact in the hospital; to create a destination for health and to be that hub for the community and the state,” he concluded. “As the only academic health center in the state, we have that obligation to provide for everybody in Indiana, and particularly in our neighborhood in Indianapolis."

Posted by

Collaborate with your Peers!

HealthSpaces is a community for people that plan, design, build and operate spaces where healthcare is delivered.

June 7-9, 2026 | Braselton, GA

Learn More

-4.png)

-Dec-09-2025-05-48-44-4379-PM.png)

-4.png)

-1.png)

-2.png)

Comments