The Texas Medical Center in Houston, Texas isn’t exactly short on space. With 50 healthcare institutions spanning 50 million square feet, it’s the eighth largest business district in the world, employing 100,000 workers and serving 10 million patients annually.

And yet despite its immense size, the Texas Medical Center is still growing. At Texas Children’s specifically, the Pavilion for Women has undergone a considerable expansion in the last several years, one made all the more impressive by the fact that it consisted entirely of leveraging existing capacity.

“This building, when it was built, was built completely out,” said Gaurav Khadse, Texas Children’s Assistant Vice President of Facilities Planning & Development, at HealthSpaces. “There were very few shell spaces that were there – about 20 percent – and over time, those shell spaces have filled up, too.”

During his presentation, Khadse explained how Texas Children’s increased its inpatient capacity without building any new floors, and discussed what strategies helped it mitigate the challenges of this approach.

Going Up?

The Pavilion for Women was designed to be a “one-stop shop” for women’s health, from obstetrics and gynecology to menopause care and everything in between. At 16 stories tall, the building’s outpatient clinics, inpatient beds, and NICU facilities support approximately 6,500 deliveries every year (about one every 20 minutes). To increase that to 8,500 by 2030, Texas Children’s would have to expand the building – right?

Well, maybe not.

As Khadse explained, expanding vertically would mean adding not only the four floors necessary to reach the 2030 goal, but the building’s full capacity of eight additional floors. Right off the bat, that means Texas Children’s would be paying for four shell floors. It would also have to disrupt operations on every other floor by building a high-rise elevator, not to mention the operational impacts brought by a crane right at the building’s entrance, a hoist, garbage dumpsters, fencing, and all the other logistics. The price tag for all this came out to $300 million – a pre-COVID estimate, of course.

They decided to leverage their existing space and move their clinics out to an office building.

The next question, then, was what exactly it would take to fully leverage the building’s existing space. Khadse’s team started by evaluating its operations and identifying bottlenecks caused by a lack of sufficient triage beds. Then they looked at whether they could move any of its clinics into adjacent buildings – perhaps the Main Tower, an office building across the street – and then fill in the newly empty spaces with patient beds.

"So we decided, well, that is a good strategy," Khadse said. "Let's leverage our vacant space. Let's move our clinics out to that building."

Main Tower rebranding and clinic relocations

The solution ended up being a three-phase plan: increase triage space in the Pavilion for Women, while identifying and repurposing other underutilized spaces; move generalist practices to the Main Tower, and backfill those newly vacant spaces in the Pavilion with inpatient services. The total cost of this approach, set for completion by 2025, ended up at about $201 million, a respectable $100 million cheaper than expanding vertically.

In Pod We Trust

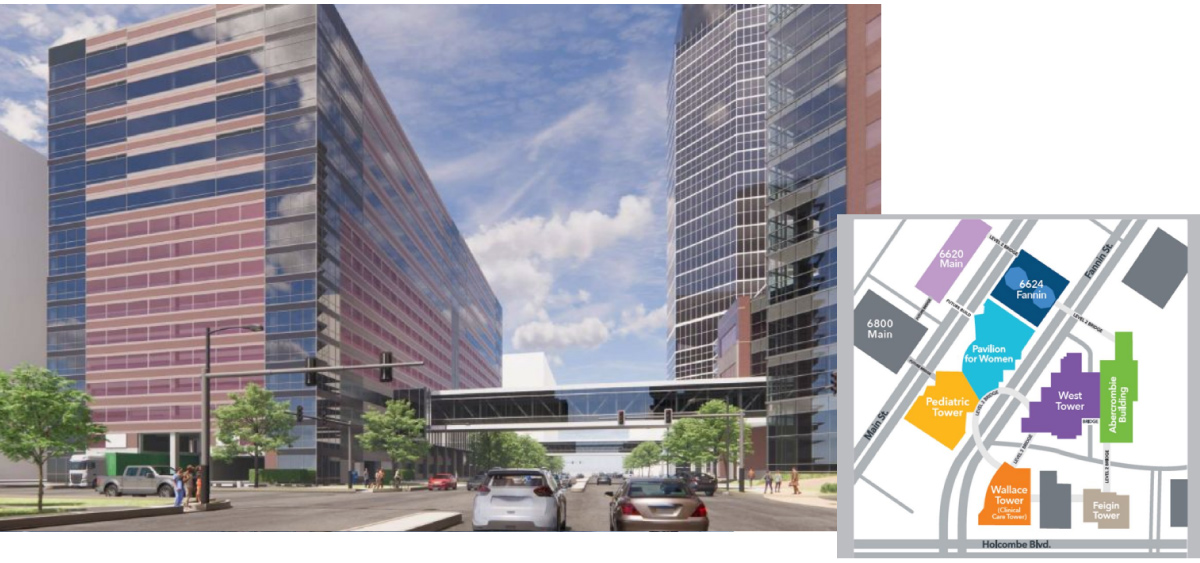

One crucial aspect of this strategy was preserving both the Texas Children’s aesthetic in the new building, and the overall “one-stop shop” experience for patients. “In order to do that, of course, we came up with a design that blended in with the rest of the campus,” Khadse said. “But the most important thing was we had to build a bridge that connected it to the pavilion so it looked like a seamless experience, as well as a connection to the existing building.”

Main Tower Clinic Pod

Inside the Main Tower itself, the next challenge was converting a massive, 40,000-square-foot open floor plan into a boutique healthcare experience. Khadse’s team settled on a standardized approach, in which a main reception area funnels patients into one of numerous identical pods, each with its own sub-waiting room, exam rooms, offices, and workstation.

“Every pod will have its own identity in the form of color, wayfinding, graphics, as well as identification," Khadse said. "Each pod has six exam rooms with two offices, so the providers can work the three exam rooms, and then if they want to expand, they can go to the next pod.” One floor has pods with nine exam rooms in a slightly different design, but the rooms themselves are all the same.

Clinic Pod, Sub Wait and Wayfinding

Having completed phases one and two, Khadse’s team is currently deep in phase three: backfilling inpatient services. "We've looked across the continuum of care again to see what we need to increase and we’re being very thoughtful about not creating bottlenecks by increasing just one service line,” he said.

Raising that annual delivery figure isn’t simply a matter of adding LDR and postpartum beds; it also requires mindfulness of rate limiters, like whether there’s enough space to add NICU beds in kind. “We’ve been looking at that very carefully,” Khadse said. “Data has been our friend.”

In closing, he acknowledged that while phase three has seen its share of escalation challenges, he’s still hopeful the project will be complete by the end of 2025.

Posted by

Collaborate with your Peers!

HealthSpaces is a community for people that plan, design, build and operate spaces where healthcare is delivered.

June 7-9, 2026 | Braselton, GA

Learn More

-4.png)

-Dec-09-2025-05-48-44-4379-PM.png)

-4.png)

-1.png)

-2.png)

Comments